Dr Kay Standing

Discussing menstrual health in Nepal

One of the pressing issues that the 2015 earthquakes in Nepal drew our attention to was the difficulties faced by women in accessing products to manage their periods with dignity.

Following the earthquakes, we were approached by a number of small charities to evaluate the impact of the work they were doing to address this problem. Funded by the British Academy, over the past 18 months we have visited Nepal and interviewed a wide range of Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) and activists who are working to promote menstrual health awareness.

For the past 25 years, we have been promoting gender based equality in Nepal and we hope our research findings will share good practice among stakeholders and influence policy in the country.

Dr Sara Parker

There has been widespread media attention on Chapaudi – where menstruating Nepalese women are confined to a cow shed or a makeshift hut. This cultural practice can place the women in severe danger as they face, and frequently die from, brutally hot temperatures and carbon monoxide poisoning from fires lit to keep warm during winter, as well as rape.

However, despite progress in making this practice illegal, our research highlights that there are a wide range of menstrual stigmas and taboos in Nepal, from not being able to cook, participate in religious ceremonies or even touch your husband.

There is also a lack of knowledge about the reproductive cycle. Sex education in schools is limited and fails to address the social stigmas around menstruation. In addition many women and girls, especially in more remote areas, lack the means of managing their periods with dignity.

Many women in remote rural areas use old saris or cloth rags, or free bleed. Lack of awareness of menstrual hygiene management has led to the repeated use of unclean cloths or improperly washing, drying and storing cloths, which can cause urinary tract infections.

Our research found evidence that attitudes are changing. Also the country has a strong network of NGOs and activists providing menstrual hygiene kits and education to challenge social customs and taboos. We spoke to organisations working in a range of sectors, from health, education and gender equality to women entrepreneurs, who are trying to provide both education and better menstrual products.

Many of these organisations distribute or produce menstrual hygienic kits, containing reusable pads made from waterproof, antibacterial and antifungal material that can be cleaned with soap. These are usually provided as part of a kit, including pads, soap, underwear and a carry bag. When washed and dried correctly pads can be used for up to three years.

Science class on menstrual health in Nepal

Reusable pads are less expensive in the long-term and are more environmentally-friendly than disposable pads. These are aptly named dignity kits, freedom kits or menstrual management packs – rather than using terms such as ‘sanitary’ or ‘hygiene’ – to break the link with periods being seen as impure and dirty.

As part of our research, we surveyed 286 girls and women using the pads. They told us that they were comfortable, didn’t leak, and, when combined with adequate toilet and washing facilities had some positive impact on girls’ school attendance.

However, more important are the education programmes which support the distribution of re-usable pads. These not only provide knowledge on the menstrual cycle, but by including members of the wider community, can raise awareness and challenge menstrual taboos.

A ‘dignity’ or ‘freedom’ kit

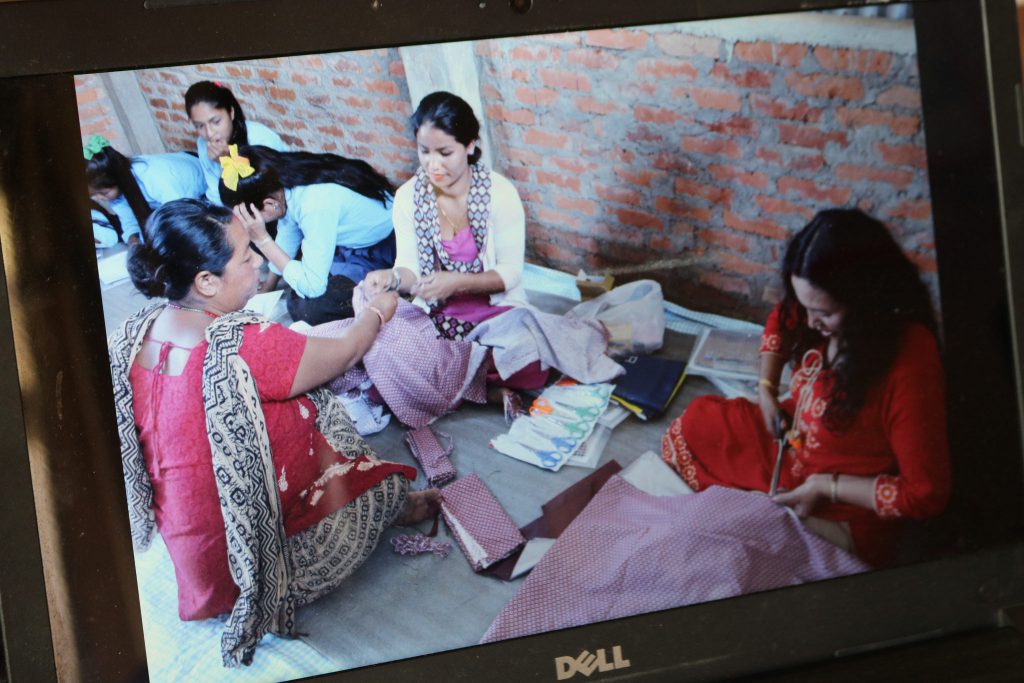

Many organisations are training women and girls to make their own kits. As well as being more sustainable, this has the potential to provide income generating opportunities for women. While donated kits play an important role in emergencies and those areas where women are too poor to buy products, they can undermine local production. A word of warning is needed here as the pads need to be high quality in order to be effective and not seen as a substandard alternative to commercial disposable pads.

Pads alone will not challenge cultural practices. But progress is being made and the work being done by menstrual activists in Nepal is beginning to impact on attitudes and knowledge.

We are now working on feeding back our findings at the local level so that good practice can be shared amongst stakeholders and findings can be used to influence policy. Materials and stories from local organisations in Nepal can be used within the school curriculum and teacher training to ensure girls and boys have access to better sexual health education. Community level awareness and education programmes are also needed to spread these messages across generations

As our research highlights, the work being done by gender activists in Nepal is going a long way to ensure no one is denied the right to a dignified period.

We are publishing this blog to mark International Women’s Day on Thursday 8 March which this year’s theme is #pressforprogress